I recently decided that my many bookcases needed to be “reorganized”

and that at least a few of my hundreds of books might be given away or donated to the

local library. The latter didn’t happen, of course I kept everything, but in

the process of organizing books by subject and author, I discovered that I have

a substantial collection of chapbooks. Coincidentally, a few days later, I read a great chapbooks article in

THEthe Poetry Blog by my good friend and colleague Michael T. Young.

A chapbook is a mini collection of poetry, typically no more

than 20-40 pages in length. Many chapbooks center on specific themes and are

generally saddle-stitched (stapled like a pamphlet or magazine). They are suited

to small print runs and can serve as effective introductions to your work.

I know many poets who have chapbooks among their credits. Many of these are beautifully designed and produced and contain superb poems. If you have a small collection of poems that work well together and

form a cohesive “collection,” you may want to consider looking for a chapbook

publisher. Sometimes less really is more!

One of the chapbooks in my collection is a chapbook on chapbooks that I

wrote for Muse-Pie Press in 2009. To get an idea of the chapbook's historical relevance in literature, I thought you might be interested

in reading excerpts from that little book (after reading Michael's article, of course).

__________________________________

The following is excerpted from Chapbooks: A Historical Perspective,

Muse-Pie Press. Copyright

© 2009. All rights reserved.

A chapbook is, by definition, a small book or pamphlet that contains

compact literary works. Originally called “small books” or “merriments,” the

term chapbook, coined by nineteenth

century bibliophiles, came into familiar usage long after this type of book

became popular. The root word chap

derives from the Old English word cēap

that referred to trade.

Interestingly, chap was first applied

not to the books but, rather, to the men who sold them.

Beginning during the 1500s, small books were sold by itinerant peddlers

called chapmen (also colloquialized

as cheapmen) who traveled through

England’s rural villages typically hawking their wares door-to-door, on street

corners, and at markets and fairs. Most carried these small-sized, easily

portable, and inexpensive books in boxes and sold them for a groat or less each

(a groat was a British silver fourpence piece used in trade during the

fourteenth through seventeenth centuries). Chapmen were characteristically

nomadic, wayward figures who lived on the margins of society. The typical

chapman was described in an 1890 Harper’s

Magazine article as one who “stood in the social plane upon neutral ground

between respectability and roguery…living the irresponsible life of a gypsy….”

Early chapbooks were waistcoat pocket-sized

and crudely made. Usually produced from rag paper and printed on both sides,

they were folded to resemble small books and simply stitched with the outside

pages serving as covers (special cover stocks were not typically used, making

the first chapbooks distinctively coverless). For the most part, early

chapbooks were produced in printings of eight, twelve, sixteen, or twenty-four

pages.

Concurrent with chapbook production were

broadsides (texts printed on one side of a single sheet of paper) and

slip-poems (printed on long strips of paper cut from larger sheets). All were

early print media products intended for the intermediate and poorer classes who

were literate enough to possess some measure of reading ability but who were

not affluent enough to afford the larger, bound books that were purchased and

prized by the wealthy.

Because chapbook readers were typically less

learned than their richer and better educated counterparts, early chapbook

content was geared to semi-literate tastes and included popular ballads and

songs, tales of medieval times, courtly love, poetry, almanacs, guides to

fortune telling and magic, political treatises, religious tracts, and sometimes

downright bawdy stories. Paper quality was of the poorest (it is reported that

early chapbooks were sometimes purchased as a paper source for wrapping and as

“bum fodder” or toilet paper), and illustrations were limited to the crudest

quality “recycled” woodcuts that were often incongruously reused in several

chapbooks regardless of their relevance to the text.

Of little interest to the elite and to the

up-market literati, chapbooks became the poorer person’s form of printed

literature, historical information (often unreliable), and entertainment.

Costly bound books were available only to the wealthy while chapbook versions

were accessible to larger numbers of people. Eminently affordable, chapbooks

became “everyman’s” literature of choice primarily by economic default.

According to Howard Pyle (Harper’s, June

1890), “Once upon a time the chapbook was as common to find in the farm-house

and the cottage as is the weekly paper or the almanac nowadays; you came upon

it at every fireside; you found it lying upon every corner shelf.”

Chapbooks figured to a significant extent in

the transition from sung ballads to printed texts as evidenced in the story of

Guy of Warwick. This story originated during the Middle Ages and was originally

sung as a heroic ballad that was widely known among all classes of people. At some

point between 1200 and 1400, it was written as a manuscript available only to

the scholarly and to the rich. During the first decades of the 1500s, it was

printed for the gentry, and later in the 1500s it was abridged into broadside

format as a ballad meant to be sung. By the late 1600s, the story of Guy of

Warwick appeared as a twenty-four-page chapbook with a target audience of lower

class readers. While the upper classes and members of established literary

circles would have seen this as a vulgarization, chapbook versions brought

Guy’s narrative to a wider readership and secured the story’s place in both

literary history and popular culture.

Chapbooks saw an increase in status between

the 1500s and the 1700s as literacy rates rose. By the 1600s there were more

schoolteachers than ever before; however, full literacy was tempered by the

need for child labor, and often young children received just enough education

to enable them to read without being able to write before they were pressed

into labor to augment family incomes. For such children, chapbooks provided a

singular source of education and entertainment.

Early chapbook popularity may be measured by

a few surviving records. It has been noted that Oxford bookseller John Dorne

documented in his 1520s day books that he had sold up to 190 ballads a day at a

halfpenny each, and as many as 400,000 almanacs were printed annually by the

1600s. In 1664, the probate inventory of printer Charles Tias (owner of The

Sign of the Three Bibles on London Bridge) included printed sheets to make

about 90,000 chapbooks and 37,500 ballad sheets. In 1707, printer Josiah Blare

(of London Bridge’s The Sign of the Looking Glass) listed 31,000 books and 257

reams of printed sheets. Such printers either sold chapbooks to chapmen cheaply

or supplied them on credit that was paid off when the books were sold.

While chapmen facilitated extensive

distribution of the first chapbooks, they also provided printers with

information on which subjects were “best sellers.” Accordingly, the trendiest

chapbooks were reprinted, edited, pirated, and reproduced in numerous editions.

Printers and publishers often issued catalogues, and some are recorded in the

libraries of provincial gentry and yeomen. Extant records suggest that

chapbooks were important to the people who owned them: in one example, Quaker

Yeoman John Whiting, while imprisoned in Somerset during the 1680s, had his

chapbooks sent from London by carrier and held in keeping for him at a nearby

inn.

The chief center of chapbook production was

London (at least until the time of the Great Fire in 1666), and most of the

chapbook printers were based in the area around London Bridge. However,

numerous smaller-city chapbook printers joined ranks with city publishers and

catered to the more rural public.

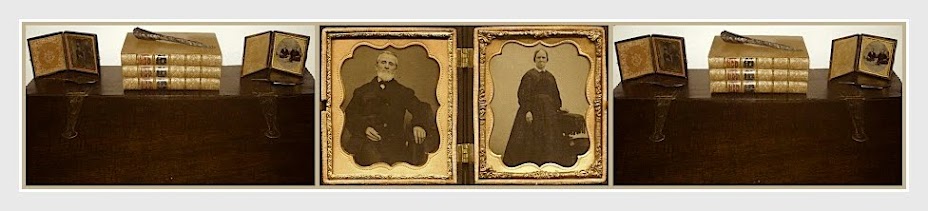

By the nineteenth century and the reign of

Queen Victoria, chapbooks entered a more modern incarnation. At that point in

its history, the chapbook was included among various ephemera or disposable

printed materials, including pamphlets, political treatises, religious tracts,

nursery rhymes, folk tales, children’s literature, almanacs, and poetry. Most

(improved in quality and appearance and with covers) were illustrated with

popular prints of the Victorian era and are an example of the commercial nature

of chapbook trade at the time.

Chapbooks also saw

a transition from adult to children’s literature during the nineteenth century.

Neuburg suggests that literate adult Victorians had outgrown their fondness for

the medieval romances and other reading material printed in earlier chapbooks

and looked for literature that would explain the rapidly changing and often

perplexing Victorian world. As adult reading preferences changed, chapbook

publishers, aware of a less interested market, began to accommodate young

readers, and chapbooks were printed to delight, entertain, and instruct

children.

During the mid-nineteenth century, industrialization brought about a

dramatic change in labor economics and with it the development of a “white

collar” non-manual working class.

The emergence of this new moneyed, middle class generated a relaxation

in class structure that admitted well-paid, working “gentry” to refined

society. Conditional with admission to polite but not refined society came

aspirations and social affectations borrowed from their social “betters.” For a

time, Queen Victoria’s ever-increasing number of children became prominent in

Victorian hearts and headlines. Consequently, an important Victorian refinement

to be cultivated was “childhood,” and the entire “estate” of childhood was

sentimentalized and cherished in art, literature, and contemporary culture.

“Childhood” required a new philosophy and

mind-set, special arrangements, special equipment, and special rules, all of

which presented an especially potent response to children’s literature – for

the less than elite and wealthy in the form of chapbooks. The middle class was

a new social phenomenon, and middle class parents paid more attention to the

diet, education, moral and social development, and entertainment of their

progeny than had hitherto been awarded. Like wealthy children, middle class

youth were better educated and child-specific reading materials were widely

welcomed. For parents who could not afford expensively bound books, chapbooks

were an acceptable substitute.

Unlike the

offspring of the wealthy and middle classes, economically underprivileged

children were not permitted the extravagances of play, immaturity, and

irresponsibility. Most poor children faced working days that saw them rise

before dawn six days a week and trudge off to paid employment in conditions

worse than those we pillory in the sweat-house factories of Third-World

countries today. They were not categorized as children but, rather, as cheap

labor, and many worked in factories alongside their parents. For those who

could at least read, chapbooks provided respite from farm, household, and

employment obligations. This, however, was not true for all working children.

Nineteenth-century publishers began to produce colored chapbooks for young

readers, often employing children to painstakingly hand-color illustrations. It

is ironic and sad (and like so much that was paradoxical in Victorian England)

that many poor children worked long, arduous hours, often in the meanest

conditions, coloring illustrations in chapbooks that were supposed to amuse and

entertain them. For children employed in the book industry, it is unlikely that

the chapbooks they worked to color brought them any pleasure at all.

Although chapbooks were especially popular in

England and Scotland, they were also published in the United States and across

the globe in such countries as Russia (where they were linked to the rise in

literacy after the emancipation of serfs in 1861). As the nineteenth century

progressed through the dawning Age of Industry and the irrevocable changes

wrought by constant innovations in production techniques, commerce, and

economy, the chapbook’s popularity began to fade. Advancements in printing

techniques and lithography, inexpensive reproduction of important artworks,

amplified production of bound books, and improved transportation systems

powered mass distribution of newspapers and periodicals and buttressed cheap

production and dissemination of hard bound books. These provided uncompromising

competition for the humbler chapbook.

Chapbooks enjoyed a more contemporary

renaissance during the latter years of the twentieth century. Promoted in part

by low-cost copy centers, chapbooks appear in huge numbers today. The term chapbook currently describes small, inexpensively-produced

books, usually about 4½ by 5½ inches in size, and saddle-stitched (stapled)

rather than hard or perfect bound.

Of special interest to poets, especially

those who have experienced the difficulty of placing poetry manuscripts with

major publishing houses, chapbooks provide an accessible and cost-effective

alternative to more conventional publishing. In response to the proliferation

of chapbooks, a number of established chapbook publishers have initiated

chapbook series and contests that focus on producing chapbooks that contain

works by both known and novice poets alike.

Today’s chapbooks offer more to entertain the

eye and refined taste than prototypes of earlier centuries did. Antique

chapbooks, however, have an artistically “organic” nature and, today, scholars

and book lovers increasingly recognize the importance of early chapbooks as

collectible documents that record cultural history. A kind of folk art, these

small books remain a time-honored literary and social tradition worthy of

preservation and protection.

__________________________________

Chapbook Publishers: